|

| World wide wine consumption is increasing |

《BBC》報導,由於全球消費者對葡萄酒的需求,大大超越其供應量,使得國際葡萄酒市場正面臨供應短缺的現象。美國摩根史坦利公司的研究報告指出,2012 年的葡萄酒需求量,比供應量高出 3 億箱。該報告形容,這是 40 年來最嚴重的供應短缺。

同時,2012 年的葡萄酒產量跌至 40 年來的最低點。葡萄酒產量在 2004 年達到歷史最高峰,當時的供應量比需求量多出大概 6 億箱。在那之後,葡萄酒產量就開始逐年減少。

摩根史坦利這份報告指出,除了 2008 到 2009 出現短暫的下跌,葡萄酒消耗量自 1996 年就以來,就一直在增加,目前全球每年消耗大約 30 億箱的葡萄酒。目前,全球的葡萄酒生產業者超過 100 萬,每年生產大約 28 億箱葡萄酒。

|

| Global wine production continue to drop |

報告預測,在目前供不應求的情況下,葡萄酒庫存量短期內會出現減少的趨勢。而長期來說,生產量下降及出口需求增加的情況下,必定會推高全球葡萄酒的出口價格。

對於葡萄酒生產量下降的現象,報告認為部份原因是由於,歐洲地區持續進行的「砍倒葡萄樹」(vine pull) 政策,及惡劣天氣。

去年全歐陸葡萄酒總產量下降10%,比 2004 年產量最高時減少了 25%。與此同時,「新世界」-美國、澳洲、阿根庭、智利、南非、及紐西蘭-的葡萄酒產量則逐年在增加。隨著歐洲葡萄酒產量的持續減少,在全球葡萄酒需求量不斷上升的趨勢下,新世界葡萄酒出口國成了最大的受益者。

報告指出,法國仍然是全球最大的葡萄酒消費國,佔了全球消費量的 12%。美國則以些微的之差,位居第 2。而美國加上消費量第 5 的中國市場,是驅使葡萄酒需求量不斷上升的主要動力。

World faces global wine shortage

The world is facing a wine shortage, with global consumer demand already significantly outstripping supply, a report has warned.

The research by America's Morgan Stanley financial services firm says demand for wine "exceeded supply by 300m cases in 2012".It describes this as "the deepest shortfall in over 40 years of records".

Last year, production also dropped to its lowest levels in more than four decades.Global production has been steadily declining since its peak in 2004, when supply outweighed demand by about 600m cases.

'Main drivers'

The report by Morgan Stanley's analysts Tom Kierath and Crystal Wang says global wine consumption has been rising since 1996 (except a drop in 2008-09), and presently stands at about 3bn cases per year.

At the same time, there are currently more than one million wine producers worldwide, making some 2.8bn cases each year.

The authors predict that - in the short term - "inventories will likely be reduced as current consumption continues to be predominantly supplied by previous vintages"

And as consumption then inevitably turns to the 2012 vintage, the authors say they "expect the current production shortfall to culminate in a significant increase in export demand, and higher prices for exports globally".

They say this could be partly explained by "plummeting production" in Europe due to "ongoing vine pull and poor weather".

Total production across the continent fell by about 10% last year, and by 25% since its peak in 2004.

At the same time, production in the "new world" countries - the US, Australia, Argentina, Chile, South Africa, New Zealand - has been steadily rising.

"With tightening conditions in Europe, the major new world exporters stand to benefit most from increasing demand on global export markets."

The report says the French are still the world's largest consumers of wine (12%).But it adds that the US (also 12%) is now only marginally second.

It also states that the US together with China - the world's fifth-largest market - are seen as "the main drivers of consumption globally".

There’s no global wine shortage

Have you heard about the global wine shortage? Of course you have: it’s been covered in pretty much every media outlet imaginable, but Roberto Ferdman’s piece for Quartz (“A global wine shortage could soon be upon us”) was one of the first, and also one of the most detailed. Still, it was the classic single-source article: it basically took one Morgan Stanley report, reproduced a bunch of the key charts, and added a clickbaity headline.

But if you look closely at the Morgan Stanley report, it starts to look less like a dispassionate analysis of supply and demand dynamics in the wine world, and more like an aggressively-argued attempt to put forward one particular investment thesis as strongly as possible. What’s more, the investment thesis is not, particularly, based on the existence of any present or future wine shortage; it’s simply trying to present the idea that demand for Australian wine exports is likely to rise, and to justify the fact that a company called Treasury Wine Estates is the bank’s “top Australian consumer pick”. (The report was written by Morgan Stanley Australia.)

Although the first chart is scarier than the second chart, even the second chart does a little bait-and-switch, which you can only find by looking at the sourcing note at the bottom of the page. The numbers for the charts come from OIV, the Organisation Internationale de la Vigne et du Vin, including the estimate for 2012 production and consumption. But the 2013 estimate, showing a modest increase in production, is not the OIV estimate; it’s the Morgan Stanley estimate. And what Morgan Stanley doesn’t tell you is that the OIV estimate for 2013 is much higher.

These charts are less polished, but are actually much more useful. (They also have different units from the Morgan Stanley charts: they’re measured in million hectoliters, which is 100 million liters, while Morgan Stanley uses million unit cases, which is 9 million liters. So when Morgan Stanley says that 300 million unit cases are used for non-wine consumption, that works out at about 33 million hectoliters.)

For one thing, the OIV charts draw sensible straight lines between points, instead of turning them into elegant curves which make the trend seem continuous. The trend is not continuous: these are

annual figures per vintage, and each vintage is a unique, separate event. What’s more, while the amount of wine that will be drunk and produced in 2013 is not yet entirely clear. So OIV gives a range of possibilities, while being reasonably certain that wine production is going to increase substantially this year, by somewhere between 7.1% and 10.5%. Morgan Stanley, by contrast, gives no rationale at all for the fact that it has a forecast which is much lower than OIV’s; indeed, nowhere in the Morgan Stanley report is its 2013 forecast ever even quantified.

Add it all up, and the OIV actually concludes, quite explicitly, that the production-consumption difference for wine will “be higher than the estimated industrial needs” in 2013, for the first time since 2007. In other words, far from entering a period of global wine shortage, it looks like the 2008-2012 period of shortage is actually ending.

This global wine shortage, then, just simply isn’t real. Don’t take my word for it: ask the wine trade. Stacy Finz of the San Francisco Chronicle asked a bunch of industry types about the Morgan Stanley report, and none of them took it seriously; Victoria Moore of the Telegraph conducted a similar operation in Europe, and came to much the same conclusion.

The Morgan Stanley report paints a picture of a long-term secular downward trend in area under vine, which is running straight into a long-term secular upward trend in global demand for wine. But reality is more complicated than that: thanks to a combination of technology and global warming, an acre of vines can reliably produce more wine, and better wine, than it ever did in the 1970s. And of course if demand for wine really does start consistently exceeding supply, then there’s no reason why area under vine can’t stop going down and start going up.

But never mind all that: the Morgan Stanley report has numbers and charts, and journalists are very bad at being skeptical when faced with such things. Even Finz’s Chronicle article, which sensibly poured cold water on the report, ends with a “Wine by the numbers” box which simply reproduces all of Morgan Stanley’s flawed figures. And besides, the debunkings are never going to go viral in the way that the original “wine shortage!” articles did.

As analysts have known since long before Henry Blodget was covering Amazon, the way to make a splash is to come out with a bold, headline-worthy thesis. Morgan Stanley did exactly that with this report, and I’m sure succeeded beyond their wildest dreams. I’m sure they’ve been celebrating their PR coup all week — probably with sparkling wine of some description.

The world is facing a wine shortage, with global consumer demand already significantly outstripping supply, a report has warned.

The research by America's Morgan Stanley financial services firm says demand for wine "exceeded supply by 300m cases in 2012".It describes this as "the deepest shortfall in over 40 years of records".

Last year, production also dropped to its lowest levels in more than four decades.Global production has been steadily declining since its peak in 2004, when supply outweighed demand by about 600m cases.

'Main drivers'

The report by Morgan Stanley's analysts Tom Kierath and Crystal Wang says global wine consumption has been rising since 1996 (except a drop in 2008-09), and presently stands at about 3bn cases per year.

At the same time, there are currently more than one million wine producers worldwide, making some 2.8bn cases each year.

The authors predict that - in the short term - "inventories will likely be reduced as current consumption continues to be predominantly supplied by previous vintages"

And as consumption then inevitably turns to the 2012 vintage, the authors say they "expect the current production shortfall to culminate in a significant increase in export demand, and higher prices for exports globally".

They say this could be partly explained by "plummeting production" in Europe due to "ongoing vine pull and poor weather".

Total production across the continent fell by about 10% last year, and by 25% since its peak in 2004.

At the same time, production in the "new world" countries - the US, Australia, Argentina, Chile, South Africa, New Zealand - has been steadily rising.

"With tightening conditions in Europe, the major new world exporters stand to benefit most from increasing demand on global export markets."

The report says the French are still the world's largest consumers of wine (12%).But it adds that the US (also 12%) is now only marginally second.

It also states that the US together with China - the world's fifth-largest market - are seen as "the main drivers of consumption globally".

There’s no global wine shortage

Have you heard about the global wine shortage? Of course you have: it’s been covered in pretty much every media outlet imaginable, but Roberto Ferdman’s piece for Quartz (“A global wine shortage could soon be upon us”) was one of the first, and also one of the most detailed. Still, it was the classic single-source article: it basically took one Morgan Stanley report, reproduced a bunch of the key charts, and added a clickbaity headline.

But if you look closely at the Morgan Stanley report, it starts to look less like a dispassionate analysis of supply and demand dynamics in the wine world, and more like an aggressively-argued attempt to put forward one particular investment thesis as strongly as possible. What’s more, the investment thesis is not, particularly, based on the existence of any present or future wine shortage; it’s simply trying to present the idea that demand for Australian wine exports is likely to rise, and to justify the fact that a company called Treasury Wine Estates is the bank’s “top Australian consumer pick”. (The report was written by Morgan Stanley Australia.)

|

| But wine is still in over-production situation |

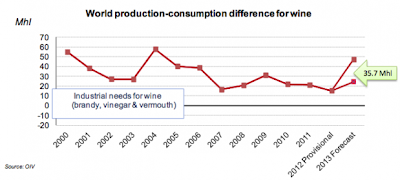

Although the first chart is scarier than the second chart, even the second chart does a little bait-and-switch, which you can only find by looking at the sourcing note at the bottom of the page. The numbers for the charts come from OIV, the Organisation Internationale de la Vigne et du Vin, including the estimate for 2012 production and consumption. But the 2013 estimate, showing a modest increase in production, is not the OIV estimate; it’s the Morgan Stanley estimate. And what Morgan Stanley doesn’t tell you is that the OIV estimate for 2013 is much higher.

These charts are less polished, but are actually much more useful. (They also have different units from the Morgan Stanley charts: they’re measured in million hectoliters, which is 100 million liters, while Morgan Stanley uses million unit cases, which is 9 million liters. So when Morgan Stanley says that 300 million unit cases are used for non-wine consumption, that works out at about 33 million hectoliters.)

For one thing, the OIV charts draw sensible straight lines between points, instead of turning them into elegant curves which make the trend seem continuous. The trend is not continuous: these are

annual figures per vintage, and each vintage is a unique, separate event. What’s more, while the amount of wine that will be drunk and produced in 2013 is not yet entirely clear. So OIV gives a range of possibilities, while being reasonably certain that wine production is going to increase substantially this year, by somewhere between 7.1% and 10.5%. Morgan Stanley, by contrast, gives no rationale at all for the fact that it has a forecast which is much lower than OIV’s; indeed, nowhere in the Morgan Stanley report is its 2013 forecast ever even quantified.

Add it all up, and the OIV actually concludes, quite explicitly, that the production-consumption difference for wine will “be higher than the estimated industrial needs” in 2013, for the first time since 2007. In other words, far from entering a period of global wine shortage, it looks like the 2008-2012 period of shortage is actually ending.

This global wine shortage, then, just simply isn’t real. Don’t take my word for it: ask the wine trade. Stacy Finz of the San Francisco Chronicle asked a bunch of industry types about the Morgan Stanley report, and none of them took it seriously; Victoria Moore of the Telegraph conducted a similar operation in Europe, and came to much the same conclusion.

- My wine-making contacts raised more than an eyebrow at the ready, steady, panic news.

- “Tell them to come to the Languedoc if they are worried,” said one. “I think I can help them out.”

- Another noted that it is still possible to buy hectares of good vineyard in parts of France and Spain for less than the cost of planting one. In other words, the price of some wine is still lower than its true cost of production, an indication that the balance of supply and demand is still favouring the demanders, not the suppliers.

The Morgan Stanley report paints a picture of a long-term secular downward trend in area under vine, which is running straight into a long-term secular upward trend in global demand for wine. But reality is more complicated than that: thanks to a combination of technology and global warming, an acre of vines can reliably produce more wine, and better wine, than it ever did in the 1970s. And of course if demand for wine really does start consistently exceeding supply, then there’s no reason why area under vine can’t stop going down and start going up.

But never mind all that: the Morgan Stanley report has numbers and charts, and journalists are very bad at being skeptical when faced with such things. Even Finz’s Chronicle article, which sensibly poured cold water on the report, ends with a “Wine by the numbers” box which simply reproduces all of Morgan Stanley’s flawed figures. And besides, the debunkings are never going to go viral in the way that the original “wine shortage!” articles did.

As analysts have known since long before Henry Blodget was covering Amazon, the way to make a splash is to come out with a bold, headline-worthy thesis. Morgan Stanley did exactly that with this report, and I’m sure succeeded beyond their wildest dreams. I’m sure they’ve been celebrating their PR coup all week — probably with sparkling wine of some description.

分析

- 由於,全球葡萄酒供應及價格是憑斷全球通縮及通膨的重要指標,以目前看全球葡萄酒供應仍過剩;全球未有通膨隱憂,卻有通縮隱憂;

- 2008 金融海嘯後,全球一直有主權債泡沫及通縮隱憂,因此,一直存在大蕭條危機;

- 目前,歐、美是以 QE 印鈔來抵抗通縮及大蕭條,但至今,全球景氣還是弱勢成長,甚致有通縮隱憂,由美國能源ETF跌破重要支撐,農產ETF將破底;

- 奇怪的是房地產價格卻自2008 金融海嘯後,房地產變貴,錢不願意投入企業創造就業率,反而進入房地產;

I have just installed iStripper, so I can watch the hottest virtual strippers on my taskbar.

回覆刪除